The most significant threat to the British public’s acceptance of the Boer war came in its latter phase, with the 1901-02 scandal over the South African concentration camps established by the British army.

How and why did the concentration camps develop? It was by way of cutting off Boer fighters in the field from food and supplies, that the British army under Lord Roberts began in March 1900 to burn the homes and crops of the farmers who were away on commando duty, leaving the inhabitants without shelter. The farm-burning policy became systematic under Lord Kitchener, who succeeded Roberts as commander- in-chief of the British forces in South Africa in December 1900. Many African settlements and crops in the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (the Transvaal) were added to the list of what was to be ‘cleared’, and Kitchener was left with the problem of the displaced.

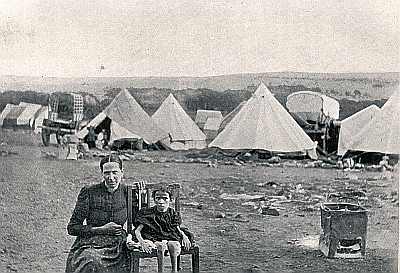

In September of that year General John Maxwell had formed camps for surrendered farmers in Bloemfontein and Pretoria, and on 20 December 1900 Kitchener officially proclaimed a South Africa-wide policy whereby surrendered farmers and their families would be housed and fed in such camps. The camps came to be used to house not only surrendered farmers but also the non-combatants displaced by farm-burning. Separate camps were established for whites and for blacks, and because the British military was unprepared to treat women and children in stationary camps differently from soldiers in temporary camps, problems soon arose with food, fuel, and general health conditions. Initially, the camps were administered much as the male prisoner-of-war camps were, and they drew little attention from the British public.

However, when these towns of bell-tents came to be overwhelmingly populated by women and children, women in Britain began to take a special interest in them. When in the autumn of 1900 women in the anti-war South Africa Conciliation Committee read about the camps, they took the traditionally feminine step of collecting clothing, blankets, and money for the camp inhabitants and organised themselves into the separate South African Women and Children’s Distress Fund. Distress Fund member Emily Hobhouse sailed out to the Cape in January 1901 with the goods and money, to distribute clothing and food among camp inhabitants on behalf of the Fund. Hobhouse, who had no parents and no husband, was a natural choice. She had travelled to Minnesota a few years before to engage in temperance and social work with what she thought was a Cornish mining community in the city of Virginia (in fact, she found no Cornishmen there, but she stayed on anyway). Both the Minnesota and the South Africa journeys were missions in line with the philanthropic expectations of Victorian upper-class women such as Hobhouse. But the South Africa project was especially important, for where women and children were in distress, it was women’s help that was needed.

Hobhouse was not the only British visitor to report: Joshua Rowntree had described his trip to the concentration camps in the Daily News, owned by fellow-Quaker George Cadbury. Rowntree’s judiciously worded reports contrasted with Emily Hobhouse’s letters home, which were printed in the Daily News and in the Manchester Guardian. While both visitors were careful not to blame individual officers for conditions in the camps, Hobhouse told of directly intervening to try to improve squalid conditions. And the Distress Fund was careful to point out in the press that ‘the military authorities have shown themselves willing to adopt some of the various suggestions which her woman’s wit has enabled her to put forward on behalf of her suffering sisters’.’ Hobhouse’s publicity from the very start emphasised her gender. For Hobhouse, the camp system itself was a gendered one. Its problems were due largely to ‘crass male ignorance, stupidity, helplessness and muddling’, she declared in her first month of visiting the camps.

Hobhouse seemed in those early days to have been willing to excuse the ‘male’ ignorance as that of sorry little boys: “I rub as much salt into the sore places of their minds as I possibly can, because it is good for them; but I can’t help melting a little when they are very humble and confess that the whole thing is a grievous and gigantic blunder and presents an almost insoluble problem, and they don’t know how to face it.”

In June 1901 Hobhouse returned to Britain and published her Report of a Visit to the Camps of Women and Children in the Cape and Orange River Colonies, a dramatic expose of the unhealthy conditions and high death rates in the camps, relying heavily on transcriptions of Boer women’s stories of their deportation and imprisonment in the camps. The report was picked up by anti-war newspapers such as the Manchester Guardian and the Daily News, and Hobhouse embarked on a national speaking tour. In response to the public stir created by the Hobhouse revelations, War Secretary St.John Brodrick appointed suffragist Millicent Fawcett to assemble a committee of women to go out to South Africa to investigate the camps and initiate reforms. Conditions started improving in the camps late in 1901, after the Colonial Office took over the administration of them from the War Office.

By the end of the war, however, 28,000 whites, mostly women and children, had died in the Boer camps – more than twice the number of men on both sides killed in the fighting of the war. The death rates were even higher in the African camps, which did not benefit from the publicity given to the white camps; 14,000 died in the camps for Africans, of a total of 115,000 internees. The British decision to clear the Transvaal and Orange Free State and deport Boer women and children and African men, women, and children into camps had not been well considered. The original camps for surrendered farmers had been expanded because, Kitchener said in a 20 December 1900 cable to Brodrick: ‘Every farm is to [the Boers] an intelligence agency and a supply depot so that it is almost impossible to surround or catch them’. The inhabitants of these farms were largely women and children, most men being out on commando. Kitchener therefore decided, in order ‘to meet some of the difficulties’, ‘to bring in the women from the more disturbed districts to camps near the railway and offer the farmers to join them there’. So Kitchener saw himself as solving a military problem by deporting women from their farms and establishing the concentration camps. The first lot of white women was brought into the camps to stop them from spying for the Boers.

After the early stages of the war, however, white and black families appear to have been brought in because the British had confiscated or burned their homes and food. Kitchener was not concerned about how the camps would be received by the British public, the Boers in the field, or newspapers on the European continent. Those public relations problems fell to Brodrick. In March, after questions in Parliament forced Brodrick to cable Kitchener for information about the camps, Kitchener was reassuring about the need for the camps: ‘The refugee camps for women and surrendered Boers are I am sure doing good work[;] it enables a man to surrender and not lose his stock and movable property . .. The women left in farms give complete intelligence to the Boers of all our movements and feed the commandos in their neighbourhood’.

Just over a week before, when asked by John Ellis whether ‘the persons in those camps [were] held to be prisoners of war’ and by Irish M.P. John Dillon ‘Are they guarded by sentries with bayonets?’ Brodrick had told the House of Commons that ‘these camps are voluntary camps formed for protection. Those who come may go’. Why didn’t the War Office from the first admit that the camps were established to keep the Boer women from passing intelligence along to the commandos? In admitting that, they would have been admitting that the women were imprisoned because of their military activities, were in fact, as the Liberals and the Irish M.P.s were saying, prisoners of war. Part of the reason for their reticence was that Brodrick had been virtually in the dark about the camps himself since the formation of the earliest ones in September 1900. Information was extremely slow in coming from the close-mouthed Kitchener, and Brodrick does not appear to have known whether or not women could leave the camps. In the March 1901 exchange in the Commons, Brodrick clearly had not settled on the way in which the camps should be portrayed. When the War Secretary admitted, ‘A certain number of women had been deported to the laager [camp]’, Dillon, to loud Irish cheers, asked, ‘What civilised Government ever deported women? Had it come to this, that this Empire was afraid of women?’ Brodrick stepped deeper into it when he responded: ‘Women and children who have been deported are those who have either been found giving information to the enemy or are suspected of giving information to the enemy’. An outraged Dillon returned: ‘I ask the honourable gentleman if any civilised nation in Europe ever declared war against women. . . . A pretty pass has the British Empire come to now!” The Government soon stopped referring to the deportation of women and children, and Brodrick no longer talked about having to imprison Boer women to keep them from spying. But the opposition, in Parliament and in the press, continued to harp on the women’s status as prisoners until, at Emily Hobhouse’s recommendation in June, Brodrick agreed to allow camp inhabitants to leave if they had relatives or friends to go to. He wrote to Kitchener on 21 June that ‘Our line has been that they are not penal but a necessary provision for clearing the country of people not wanted there and who cannot be fed separately. In consequence if you can allow any who can support themselves to go to towns so much the better’. Brodrick knew that he had to find a workable ‘spin’ for the public; presenting the camps as penal institutions for female spies would not do. The camps needed justification while other aspects of the war did not. Farm-burning, for example, never prompted the kind of protests that surrounded the camps. The sides on farm-burning broke down into pro-Boer versus pro-war, as few people who supported the war were prepared to quarrel with the methods by which Roberts and Kitchener were fighting it. But the camps were another matter. The Great British Public could agonise about the death rates and the conditions in the camps without being seen to criticise the generals, the soldiers, or the Government’s war policy. While farm-burning was military strategy, the camps could be seen as a humanitarian issue. Farms, after all, were fields and buildings, but camp inhabitants were people.

Brodrick noted as early as April 1901 in a letter to Kitchener that ‘some of our own people are hot on the humanitarian tack” on the subject of the camps. In May, Brodrick noted that he was preparing papers for the House on farm-burning and the camps. For farm-burning, he had ‘arranged so as simply to show the farms-dates- cause [for the burning]’, as if a such a list would be sufficient to justify each case. But he was a bit more worried about the camps

because we have a demand from responsible people headed by some MPs to allow (1) Extra comforts to be sent in (2) some access by responsible and accredited people who can assist in measures for improving the life in the camps (3) some latitude as to visitors – friends of the refugees.

Brodrick was prepared to go along with points 1 and 2, especially because

‘they have also shown considerable discretion as they have had and communicated to Govt some harrowing accounts of the condition of the earlier camps (Janr. & Febr.) and have not used them publicly’.’

Kitchener’s reply was:

I do not think people from England would be any use or help to the families in camp as they already have a number of people looking after them but funds might help them if properly administered. I wish I could get rid of these camps but it is the only way to settle the country and enable the men to leave their commandos and come in to their families without being caught and tried for desertion.

Kitchener, then, saw the camps almost exclusively in terms of their function in getting farmers to surrender. Meanwhile the camps, as Brodrick indicated, were being discussed in Britain strictly in terms of their women and children inhabitants. Kitchener continually brushed off attempts from the War Office to address the camps in such terms. Brodrick was forced to press the point with Kitchener for the sake of public opinion:

If we can get supplies and interest in these unlucky people we shall not only still public feeling here, but smooth the path for the future. I imagine the returns from St. Helena &c will be much affected in temper by the care taken of their women kind.”

The opinions of the camp inhabitants themselves did not worry Brodrick; the South African public opinion about which he worried was the opinion of the Afrikaner men. Public opinion in England, however, appeared also to include women of the upper classes – ‘responsible people’ such as Mary Ward. And while Brodrick had hoped that the Boer prisoners of war returning to South Africa after the war would be ‘much affected in temper by the care taken of their women kind’, in fact the farmers were horrified at the huge number of deaths in the camps. Relations between Britain and white South Africa were soured by memories of the camps for decades to come.

Except for a few pro-Boers, the people of Britain had proved willing to believe the best about the necessity for the war in the first place. But the War Office was not sure the British public would stand for its military locking up white women wholesale to keep them from spying or herding women and children into camps because it had destroyed their homes and livelihood. If the British were going to imprison the Boer women and their children, they were going to have to do it within a discourse consistent with nineteenth- century ideology about gender relations: Brodrick structured it around the idea of ‘protection’. By establishing the camps, the argument ran, British men were adopting the duties shirked by the unmanly Boers on commando who had ‘deserted’ their families, leaving them to starve.’

Not everyone agreed that such protection should be the job of the British army. The Daily Mail, fierce in its support for the war, stressed the bitterness of the Boer women and their anti-British activities. War correspondent Edgar Wallace had no fear of offending women or those who wished to accord them special status:

There have been many occasions since the war started when I have wished most earnestly that the friends of emancipated womanhood had had their way, and that the exact status of woman had been made equal to that of man. I have often wished her all the rights and privileges of her opposite fellow . .. to be honoured for her gallantry – and shot for her treachery. Especially to be shot for her treachery. . . . Women have played a great part in this war, not so much the part of heroine as of spy. … We have decided that we do not make war upon women and children, and if through ill-nature women and children make war on us, we loftily refuse to acknowledge they are making war.

Boer women were ‘ill-nature[d]’, unnatural. British women, it was understood, would not make war. The Boers were seen as primitive, unchanged since their arrival in South Africa from Holland two hundred years earlier. This put them lower on the scale of civilisation than the British, different in what would have been seen as a racial way while they were also a different class – a nation of peasants. The Boer women in the camps were compared to British peasants of the seventeenth century as well as to ‘our poorer classes’ by British commentators on the concentration camps. Boer women may have been closer to nature than were European women, in Social Darwinian terms, but they were acting against the nature of women when they made war.

While the jingoist journals called the Boer women spies and complained about the ‘comforts’ of the concentration camps, campaigners for the elimination of the camps consistently tried to point out the ideological discrepancy of the Government refusing to name the women as prisoners of war while it was nevertheless keeping them confined to the camps. The Manchester Guardian and the Daily News often referred to the camps as ‘prison camps’.

Once the mortality figures from the camps began to come to light in Britain, the Daily News escalated the terminological battle by labelling the camps ‘death camps’. Emily Hobhouse criticised the military and the jingoist papers: ‘Their line generally is to speak of “refugee” camps and make out the people are glad of their protection. It is absolutely false. They are compelled to come and are wholly prisoners’. Hobhouse often referred to the camps as the ‘women’s camps’ or the ‘women and children’s camps’. While anti-war writers agitated for the camp inhabitants’ freedom to go to friends or to return to what was left of their farms, Kitchener maintained the necessity of keeping the women confined for military reasons.

But the rhetoric in London had shifted to emphasise the camps’ humanitarian function. The Times reminded readers that ‘to release most of these women now would be to send them to starve and to expose them to outrages from the natives which would set all South Africa in a flame’. Thus the discourse of the Government and the Government-supporting press brought together two ideologies of Victorian Britain – that of the weakness of woman and that of the sexual savagery of the black man towards the white woman. Black women figured hardly at all in these writings about the camps – no category existed for them, since ‘women’ were white and ‘natives’ were men. This language about the protection of white women had of course been employed earlier in British imperialism, notably in British reaction to the British deaths at Cawnpore. Sexual atrocities against British women were commonly attributed to the Indian mutineers, even after investigations had disproved such allegations.

The rhetoric used racism to produce a particular chivalric reaction in the British male. Advocates of the camps used the image of white womanhood in danger to justify a system that proved deadly to just those women it claimed to be protecting. But it was not only the defenders of the camps who spoke of the need of white women for protection from black men. One of the central themes of Emily Hobhouse’s The Brunt of the War and Where It Fell is the cruelty of the British military for subjecting Boer women to humiliation at the hands of ‘Kaffirs’. Hobhouse quotes a petition from Boer women in the Klerksdorp camp, citing the circumstances of their being brought in: When the mothers were driven like cattle through the streets of Potchefstroom by the Kaffirs, the cries and lamentations of the children filled the air. The Kaffirs jeered and cried, ‘Move on; till now you were our masters, but now we will make your women our wives’.

Hobhouse works on the same assumption that Brodrick was using – white women need protection, by white men and from black men. But Hobhouse turns the application of the idea against the Government. Yes, white women need protection; but you white men are putting them in more danger rather than protecting them. Hobhouse and the opposition and Irish M.P.s shared that conviction that white women required special treatment. ” In addition, Hobhouse and the pro-Boers also declared that women were both incapable of taking care of themselves and incapable of posing a threat to the British army. ‘Had it come to this’, Dillon had asked, ‘that this Empire was afraid of women?’ What kind of man was John Bull that he had to lock up women as a threat to his military? Millicent Fawcett, assigned by Brodrick to investigate the concentration camps on behalf of the War Office, refused that rhetoric of protection entirely. She had been a good choice for the Government. Fawcett had no credentials in either public health or colonial matters, but she was efficient, she believed in the necessity for the war, and she was well-known for being an advocate of women’s rights.

In addition, Fawcett had made up her mind that the camps were necessary before she set off for South Africa. In early July she wrote an article for the Westminster Gazette, criticising Hobhouse’s report and asserting that the creation of the camps was ‘necessary from a military point of view’. Fawcett said nothing in her article about the camps protecting Boer women and children. She was firm in her assertion that Boer farms had been centers for supplying correct information to the enemy about the movements of the British.

No one blames the Boer women on the farms for this; they have taken an active part on behalf of their own people in the war, and they glory in the fact. But no one can take part in war without sharing in its risks, and the formation of the concentration camps is part of the fortune of war.

After her July 1901 meeting with St.John Brodrick for orientation before her voyage to South Africa, Fawcett recorded in her diary that Brodrick had said ‘it was the first time in the history of war that anything of the sort had been attempted – that one belligerent should make himself responsible for the maintenance of the women and children of the other’.

But she never adopted the War Office’s line on the function of the camps as protection for the Afrikaner families. She maintained that the camps were a military necessity. The women had taken an active part in the war on behalf of their country, as was only right, and they must take a share in the consequences, as their men did. Fawcett’s feminism would not allow her to subscribe to the view of the War Office and of the anti-camps lobby. But her jingoism would not allow her to apply her feminism to a sympathy with the position of the Boer women. She did not blame the Boer women for their spying, but she did, in her Blue-book on the camps, blame them for the deaths of their children. Fawcett set out on her camps investigation suspicious of anyone who might be pro-Boer; she accepted no help from people in South Africa who had been associated with Hobhouse on her visit. When she met members of the Ladies Central Committee for Relief of Sufferers by the War, she recorded in her diary:

I led off by asking if they were non political but I quickly found they were intensely pro Boer. They recited various tales of horror. . . . I said our commission was non political.. . . Mrs. Purcell said how could our com- mission be considered non political if Miss Waterston [a fierce anti-Boer] were on it. I replied of course we all knew that Miss W had strong political views but she was capable of seeing and advising in matters relating to sanitation, diet, etc without bringing in political considerations.

For Fawcett, then, sanitation and diet, as domestic concerns, were apolitical. Apparently, Fawcett considered those with ‘strong political views’ on the other side of the issue, such as Hobhouse, as incapable of advising in such matters. Fawcett’s report included numerous accounts of Boer mothers using folk remedies for their ailing children, remedies that appeared ludicrous and dangerous to the commission. One oft-cited passage reports a Boer mother covering her child with green paint. Hobhouse liked to refute that example in her speeches, pointing out that the ‘green paint’ was only a herbal medicine mixture. In addition, the report blamed Boer mothers when they refused to let their children be taken into camp hospitals.

Fawcett ranked the causes of camp mortality: ‘1. The unsanitary condition of the country caused by the war. 2. Causes within control of the camp inhabitants. 3. Causes within the control of the administrations.’ It was to cause number two that the commission gave the most graphic evidence, and the jingoist press naturally seized upon it. One particular passage cropped up again and again in speeches, letters, and newspaper articles aimed at vindicating the British Government for the death-rates:

Even at the best of times, and especially if anyone is sick in the tent, the Boer woman has a horror of ventilation; any cranny through which fresh air could enter is carefully stuffed up, and the tent becomes a hot-bed for the breeding of disease germs. It is not easy to describe the pestilential atmosphere of these tents, carefully closed against the entrance of all fresh air. The Saxon word ‘stinking’ is the only one which is appropriate. . . . It is, therefore, no wonder that measles, once introduced, had raged through the camps and caused many deaths; because the children are enervated by the foul air their mothers compel them to breathe and fall more easy victims to disease than would be the case if the tents were fairly ventilated.

Fawcett cites many ‘unsanitary habits’ of the Boers, including ‘the fouling of the ground’, a particular bugbear of hers. ‘The inability to see that what may be comparatively harmless on their farms becomes criminally dangerous in camps is part of the inadaptability to circumstances which constitutes so marked a characteristic of the people as a race’, writes Fawcett.

Her report reveals a woman appalled at the people she is describing, yet struggling to appear even-handed. When she complains of the Boers giving inappropriate foods and strange home-made medicines to sick people, she notes:

This is a difficulty with which every doctor in England is familiar, and, with regard to the character of the Boer domestic pharmacopoeia, no doubt parallel horrors could be found in old-fashioned English family receipt books of 150 or 200 years ago. But whatever parallels can be found, or excuses made, for these practices, we are bound to take them into account. A large number of deaths in the concentration camps have been directly or obviously caused by the noxious compounds given by Boer women to their children.

Fawcett must double-remove Afrikaner women from the English: Boers are even more old-fashioned than the average English seventeenth-century family. No wonder they are not fit to govern Britons. But in fact, because it was frank about the unsatisfactory conditions in the camps at the same time as it supported the war effort, the Fawcett Commission report, wrote Mrs. Arthur Lyttleton to Millicent Fawcett, ‘has apparently done the impossible and pleased everyone . Jingoist newspapers gleefully seized on the Blue-book’s anecdotal evidence of Boer ignorance, despite the overall tone of the report, which was highly critical of camp operations. The horror stories of Boer mothers took root throughout Britain, playing into the British stereotype of the Boers as a nation of ignorant peasants. Newspapers talked of the war being fought to ‘civilise the Boer’, thus linking the Afrikaaner and the African in the minds of British readers as uncivilised peoples destined to be raised out of ignorance by the British.’

An article in The Nineteenth Century focusing on British women’s emigration to South Africa noted the unsuitability of marriage between British men and Boer women:

As a rule the Boer women of South Africa are devoid of many of the qualities which are essential to make a British man’s home happy and comfortable. Cleanliness is a virtue too often foreign to the Boer character, and it is not unfrequently replaced by an ignorance of the laws of hygiene which produces habits of slovenliness both injurious to health and distasteful to British ideas.

The article cited the Fawcett report as evidence for its claims about Boer women. The Ladies Commission criticism of the Boers, focusing on the backwardness of the Boer women and their ‘filthy habits’, had much in common with the reports of British women sanitary inspectors when they recounted visits to working-class and poor homes. Fawcett, like Hobhouse, was an upper-class woman. At least part of her inability to sympathise with the Boer women was class-related. Hobhouse, however, tried to present the Boers as a society with their own class structure, comparable to Britain’s. In the Manchester Guardian Hobhouse wrote of a Mrs. Pienaar and her family, evicted from their farm. The British ‘took everything away from her – amongst other things, 4,500 sheep and goats, 150 horses, and about 100 head of cattle’. This cataloguing of wealth ended with the sad pronouncement that ‘once rich, they now have to live on charity’. Hobhouse’s sympathy with upper-class Boer women led her to sympathise with Boer racial hierarchy as well. On her return to South Africa after the war, Hobhouse’s class pride was outraged, and she wrote to her aunt about the ‘poor white’ problem in the former republics. She related the story of a particular Boer woman and her children, who ‘sit there face to face with starvation, that terrible kind which is combined with perfect respectability. … It is so awful to people of this good class to say they are in want, or even seem to beg’. Their new poverty sat even harder with the Boers, Hobhouse explained, because of their contrast with the Africans.

‘Recollect these blacks have recently been armed against them, the Boers have been at their mercy, and the Kaffirs are now living in luxury with flocks and herds, while the Boers are in penury around them’.

Emily Hobhouse attacked Fawcett’s Ladies Commission for its lack of compassion: ‘[G]reat and shining lights in the feminine world, they make one rather despair of the “new womanhood” – so utterly wanting are they in common sense, sympathy and equilibrium’. The problem with Fawcett and her Commission, according to Hobhouse, was their inability to sympathise with the Boer women in the camps. Fawcett’s advocacy of women’s rights in Britain did not, as Hobhouse noted, lead her to sympathise with women in South Africa. In fact, the only link Fawcett made between South Africa and the status of women in Britain was to equate Boer oppression of Africans with British men’s oppression of British women. Boer and African women’s positions were not comparable to British women’s, and race was not an issue in itself but a useful analogy for Fawcett’s primary concern with British women’s rights.

Likewise race arises as an issue for Hobhouse only in relation to the white women with whom she is primarily concerned, the Boers. We have seen Hobhouse’s employment of the image of the sexual threat of the ‘Kaffir’ towards white women. ‘Kaffirs’, for Hobhouse and the Boer women she quotes, are men. Only occasionally do black women feature in any of Hobhouse’s narratives, and never are they dangerous to white women. One of Hobhouse’s correspondents, a Mrs. G, described her deportation to the camps. As Hobhouse tells the story Back at Norval’s Pont the little party was separated. The Kaffirs had to go into one camp and the white people into another.

There was a strict rule against keeping any servants in the white camp, but they ventured to keep the two little orphan girls. . . . Mrs. G thereupon stated her case to the Commandant, saying, ‘They are orphans; I have had them ever since they were babies, and I am bringing them up as my own’. He was very kind, and said he would give her a permit. . . . The only stipulation he made was that they should go back to the Kaffir camp at night.

Hobhouse presents two key versions of white-black relations in South Africa at the time. In the first, blacks are hostile to whites, always waiting their chance to turn the tables on their ‘masters’, especially sexually. Hobhouse’s reports include many instances of African men gloating over Boer women in their captivity, often accompanied with sexual taunts such as those recorded in the Klerksdorp petition. In the second version of black-white relations, Hobhouse cleverly manipulates another common British idea about South Africa. One of the British Government’s justifi- cations for the war had been Boer mistreatment of Africans. By painting a sentimental picture of Boer and African mutual attachment, Hobhouse counters common horror stories about Africans being beaten and abused by their Afrikaaner employers.

At the same time she exploits another popular British idea of what white-black relations should be: Hobhouse places Boer women in the position in which the British saw themselves – the benevolent protector watching over the childlike blacks. It is interesting that Hobhouse picks an example involving black girls – probably because of the sexual complications that would be involved if she had described a strong emotional attachment between a black male servant and a Boer woman whose husband was away. And of course, Hobhouse could assume that there would be no thought of those sexual complications in a relationship between a white woman and a black girl or woman.

As the women in the war zone became factors to be taken into consideration by the military, so did the women at home in Britain. Newspapers reflected this change; after the concentration camps became news, letters to the editor appearing in the Times, the Daily Mail, the Daily News, and the Manchester Guardian increasingly came from women who were writing as women, invoking traditional images of womanhood. The women who wrote to the Daily Mail were furious about the ‘pandering’ to Boer women and children: ‘Blencathra’ noted that

It is time for the women of England to speak. Why should the Government be at the expense of sending out ladies to the concentration camps? . . . Let the ladies of this commission stay at home and visit the fatherless and the widow.

British women’s duties were at home, cried the patriotic letter-writers. Compassion is an appropriate quality in a woman, but an Englishwoman’s compassion should be directed toward the widows and orphans of British soldiers, not toward the enemy.

Not so, argued the letter writers in the pro-Boer press. ‘An Englishwoman’ proclaimed her ‘heartache’ and ‘shame’ in the Manchester Guardian after the release of Hobhouse’s report,’ and another noted that the British should ‘have pity on all children, not just those in England’. Compassion was a female trait and duty, both sides agreed. But to whom should the Englishwoman be compassionate? Traditional associations with women’s duties could be turned to the advantage of either side.

Concern over the concentration camps became the main focus of anti-war activism for the period from June 1901 through the end of the war in May 1902. The Government itself directed a large amount of public attention to the camps from September 1901 until January 1902, highlighting the efforts of the Ladies Commission. Throughout their publicity campaigns, neither the pro-Boers nor the Government focused on the official policy of maintaining the camps; both campaigns centred on the women and children within them. The image of these women and children became a rallying point in Britain – either the image Hobhouse promoted, one of starving, noble mothers with their doomed children, or the image for which Fawcett was largely responsible, one of ignorant, selfish mothers with their neglected children.

Fawcett had to blame someone for the conditions in the camps. It was unlikely that she would have pinned the blame for 20,000 children’s deaths on the children themselves, and she was certainly not going to blame the British troops or Government. That left the element of the population championed by Hobhouse – the Boer women. Hobhouse herself emphasised the plight of the women rather than the children, perhaps because of her extensive use of interviews with Boer women in her report and speeches – she tells the stories of the Boer women in their own words, then describes the women. Although they held opposite positions on the issues of the war and the concentration camps, the reports Hobhouse and Fawcett published about the camps came to virtually identical conclusions about the conditions there. The language and examples they used upheld their own positions in the debate, but the reforms they called for – including improved rations, water purification, and sanitation measures – were strikingly similar. Fawcett’s Blue-book was accepted as legitimate by pro-Government newspapers, and camp administrators acted on its recommendations, but it was called a ‘whitewash’ by some of those against the war.

Hobhouse’s report was not acknowledged publicly by the Government or its supporters in the press, although the War Office took it seriously enough to appoint the Fawcett Commission in response to it. Hobhouse often pointed to the thousands of camp deaths that occurred between the publication of her report in June 1901 and the appearance of Fawcett’s in January 1902. She noted that had her report not been undermined by the Government and the jingoist press when it was first released, change in the camp conditions might have resulted much sooner. In Hobhouse’s memoir she says that as soon as the report appeared, ‘instantly, the sentiment of the country was aroused and had it been allowed its true expression, not only would the camps then and there have been adequately reformed, but very possibly the war would also have dwindled in popularity and been ended’. Government officials feared just such an occurrence. When Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain took over responsibility for the camps from the War Office late in 1901, he wrote to Lord Milner, the South African High Commissioner, for more information with which to allay British fears about the camps:

The mortality in the Concentration Camps has undoubtedly roused deep feeling among people who cannot be classed with the pro-Boers. . . . If, immediately on the outbreak of disease, we could have moved the camps either to the ports in Cape Colony or to some other selected situation we should have had something to say for ourselves, but we seem to have accepted the mortality as natural and many good people are distressed at our apparent indifference.

It was when some of those ‘good people’ began to come out against the war itself that Chamberlain and Milner began to get nervous about the ‘wobble’ in public opinion that Milner had feared all along. Milner saw containing opposition to the camps as the key to keeping the British public behind the war: ‘If we can get over the Concentration Camps, none of the other attacks upon us alarm me in the least’, he wrote in December 1901. The decrease in the death rates towards the end of 1901 seemed to satisfy the British public, and the camps died out as a subject in the letters columns of the newspapers.

For all the justification in England of the necessity for the camps as protection for white women and children, the War and Colonial Offices felt no need similarly to justify the imprisonment of thousands of Africans. While white women were in the camps ostensibly for protection from African men, African men, women, and children were in camps simply because it was a military necessity for the British to put them there. Districts had to be cleared, so Africans had to be cleared from them. No further justification was needed and none was ever called for, not in Britain or in continental Europe, despite the fuss about the camps for the whites. The writing about the African camps, in Government reports and in newspapers, merely related information about farm work and recorded death rates, usually inaccurately. The Guardian did refer to the camps for Africans in one leader. ‘There are some who think the war a glorious thing because the Boer was so cruel to the Kaffir’, the leader noted, pointing out that ‘the Kaffir is suffering pretty heavily in these camps, but his friends make no objection’. Hobhouse never visited an African camp. Millicent Fawcett recorded in her diary no narrative about any of the black camps – only captions on photos of African camp inmates, such as, ‘Natives at work. Singing’.

The British Government’s sending out Millicent Fawcett in response to Emily Hobhouse’s report was an acknowledgement of the seriousness with which it took Hobhouse’s assessment of the camp problem as a women’s issue. It was not a male public health expert Brodrick dispatched to South Africa – it was a woman qualified because she was a famous woman. Thus Brodrick absorbed the camps, as a women’s issue, into the imperial project. Humanitarian aid to the camps had to be part of the British Government’s responsibilities, but it had to be directed by a woman. Hobhouse’s challenge to the Government accepted the terms of the Government. She did not question imperialism itself or the necessity for white men to protect white women from black men. Thus once the Ladies Commission went to South Africa and the death rates in the camps started dropping, Hobhouse was no longer a threat to the Government’s war policy. Hobhouse’s own discourse prevented her from sustaining a threat to British imperialism once the War Office had co-opted concern for the camps from the anti-war activists. Racism and class hierarchies were a part of Hobhouse’s discourse, and her sentimentalising about Boer mothers was simply the other side of Fawcett’s claims that the Boer mothers were unworthy. Nevertheless, with Hobhouse’s report, public discourse about the camps went from an argument for their military necessity – an argument in which women had no voice – to a new form in which women had the central place, the main voice.

The men in charge of public representations of the war – the War Office, the Colonial Office, the newspaper editors and M.P.s on both sides of the issue of the war itself – had been forced to change their strategies and the language they used in relation to the camps. When the camp death rates began to drop in the last months of 1901 and during 1902, the improvement was attributed by most anti-war factions to the agitations of Emily Hobhouse and by the Government to the work of the Fawcett Commission. Men had been blamed for the conditions in the camps, and women were credited for the reforms. But the women themselves had no power to order reforms and could only recommend them to male officials. The camps were a women’s issue, perhaps, but the new female discourse masked the male bureaucracy that had the decision-making power. The Boer War marked a transition in British imperialism. The capitalist roots of the imperial enterprise were beginning to show, and the faith of the average Briton in the mission of the Empire was beginning to waver. British ideas about women and about race were likewise changing and indirectly affecting imperialism. Questions of gender in writing about the Boer War arise not from the positioning of the nations involved as masculine and feminine, as coloniser and colonised, or as subject and other. Oppositions, indeed, are problematic in the case of a two-sided war for the land of a third party. Instead, the study of gender in discourse about the Boer War brings up a more complex set of relationships among male and female Britons, Boers, and Africans. These relationships appear in public and governmental writings during the war – newspapers, Blue-books, military despatches and ministry telegrams – as well as in private correspondence among public figures involved in the war.

The writings about the concentration camps describe a public controversy that encapsulates some of the difficulties with which turn-of-the-century Britons were wrestling. It was necessary for men to protect women and children; for the British to guard the interests of the childlike Africans; and for a civilised European nation to take over from the seventeenth-century Boers if the proper imperial relationship of mother country to colony was to be maintained in South Africa. But during the Boer War, especially with the controversy over the concentration camps, each of these assumptions was in negotiation. Women could suddenly be considered combatants in war. The British could not maintain a consistent posture towards those Africans in South Africa whom they had, at the start of the war, vowed to protect. And the backward nation of farmers from whose misrule the British were going to save South Africa ended by being granted self-government in the Orange River Colony and the Transvaal.

Just eight years later, rallying around an Afrikaner nationalism at least partly fueled by the memory of the thousands dead in the concentration camps, whites in the Cape Colony and Natal joined those of the former republics to become citizens of the Union of South Africa in the beginning of a new era of white government of South Africa.

Pingback: Lest we forget – Concentration Camps of the Boer War | Mrs Jones and Me

The Women’s Monument in Blomfontein was erected in memory of the women and children that died in the British camps in the Boer War. Emily Hobhouse fought for those women to be seen as universal, not parochial, and dedicated the memorial in 1913. The speech she gave was finally published by the British government in 1963 – but in edited form. The excised portion reads:

“We in England are ourselves still dunces in the great world school, our leaders are still struggling with the unlearned lesson, that liberty is the equal right and heritage of every child of man, without distinction of race, colour or sex…

We too, the great civilized nations of the world, are still Barbarians in our degree, so long as we continue to spend vast sums in killing or planning to kill each other for greed of land and gold. Does not justice bid us to remember today how many thousands of the dark race perished also in Concentration Camps in a quarrel which was not theirs?”

Fasinating @sambson. Where did you discover the excised section?